Best Practices in Teacher Pay: State Position Allotments and Hidden Teacher Pay Inequities

A comprehensive, professional compensation plan includes layered pay strategies that build on one another to ensure the recruitment and retention of a high-quality workforce. This is the twelfth in a series of blogs highlighting best practices in teacher pay featured in detail in BEST NC’s report, Teacher Pay in North Carolina: A Smart Investment in Student Achievement.

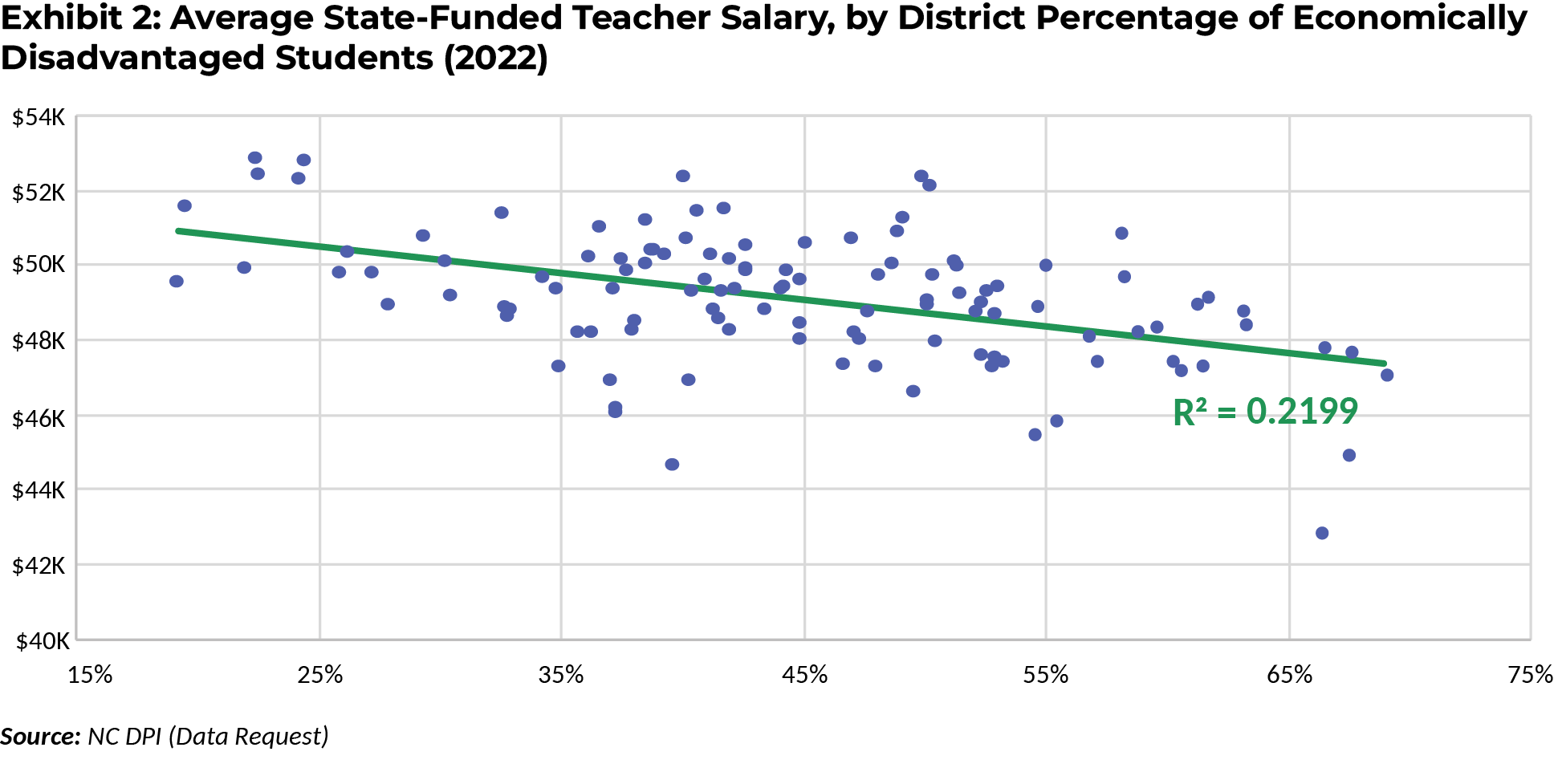

State Position Allotments

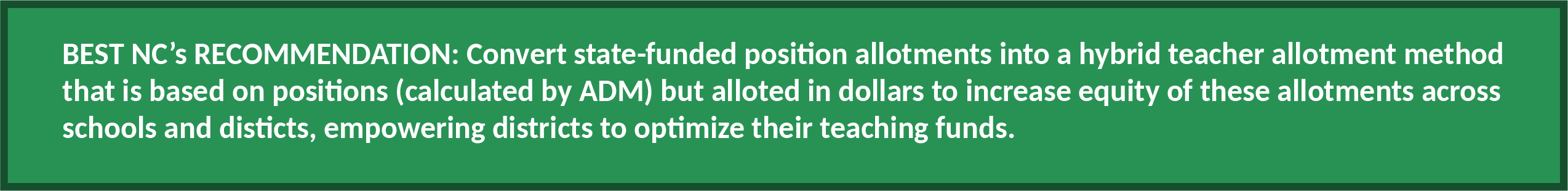

The classroom teacher allotment is – by far – the largest single state allotment: salary and benefits for instructional personnel represent approximately 58% of total state funding for education. In North Carolina, the state allots teaching positions to each school district based upon the number of students in each grade, according to ratios set by the General Assembly. When a school district hires a teacher, the state provides the district with the teacher’s state base pay, depending on where the individual falls on the state salary schedule.

In concept, the position allotment system is intended to provide equal access to teachers for all schools and districts – because the state funds positions rather than dollar amounts, districts can hire teachers without regard to how much the teacher will cost to employ.

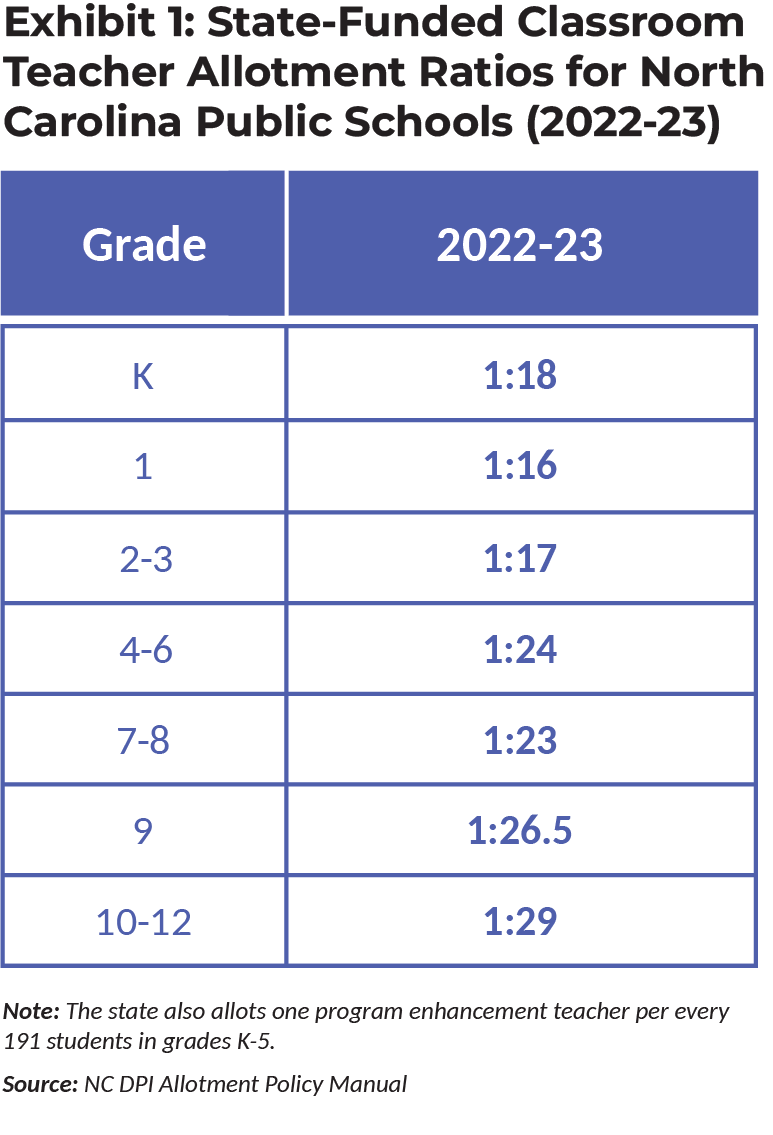

The reality is, however, that teachers are not evenly distributed across the state, and they can choose to which schools they want to apply. More experienced and qualified teachers are concentrated in more affluent schools and districts, while schools with greater percentages of economically disadvantaged students have applicant pools that are less experienced and have lower qualifications. Researchers call this phenomenon teacher sorting. So, while a district can use the allotment model to hire any teacher without regard to cost, many schools simply don’t have access to highly qualified teachers.

To put this impact into simple terms, consider two schools, each employing 100 teachers, and an applicant pool of 200 total teachers — 100 experienced teachers making $60,000 and 100 beginning teachers making $40,000. If the first school hires all 100 experienced teachers and the second school hires the remaining 100 beginning teachers, the first school will have a $6 million teacher budget, while the second school will have a $4 million teacher budget. This hypothetical example demonstrates that an equal number of teachers does not always mean equal value.

A 2016 study by the Program Evaluation Division of the North Carolina General Assembly study found that teacher sorting is exacerbated by the state’s position allotment system. The study found that the allotment system enables wealthier districts that offer higher salary supplements and greater supports for students, teachers, and families to take advantage of applicant pools rich with experienced, National Board Certified teachers to accumulate greater numbers of highly qualified teachers, depriving hard-to-staff schools with more economically disadvantaged students of access to these educators. This pattern is visualized in Exhibit 2 below.

In addition to teacher sorting – a teacher’s choice to apply to more desirable schools and districts – the differences in the strength of teacher applicant pools can also result from regional variation in teacher talent, which helps explain why the inequities are not just an ‘urban vs. rural’ or ‘affluent vs. poor’ phenomenon. A region that has a more robust supply of educators will employ the more experienced and National Board Certified teachers, thus increasing the per-teacher cost of their workforce.

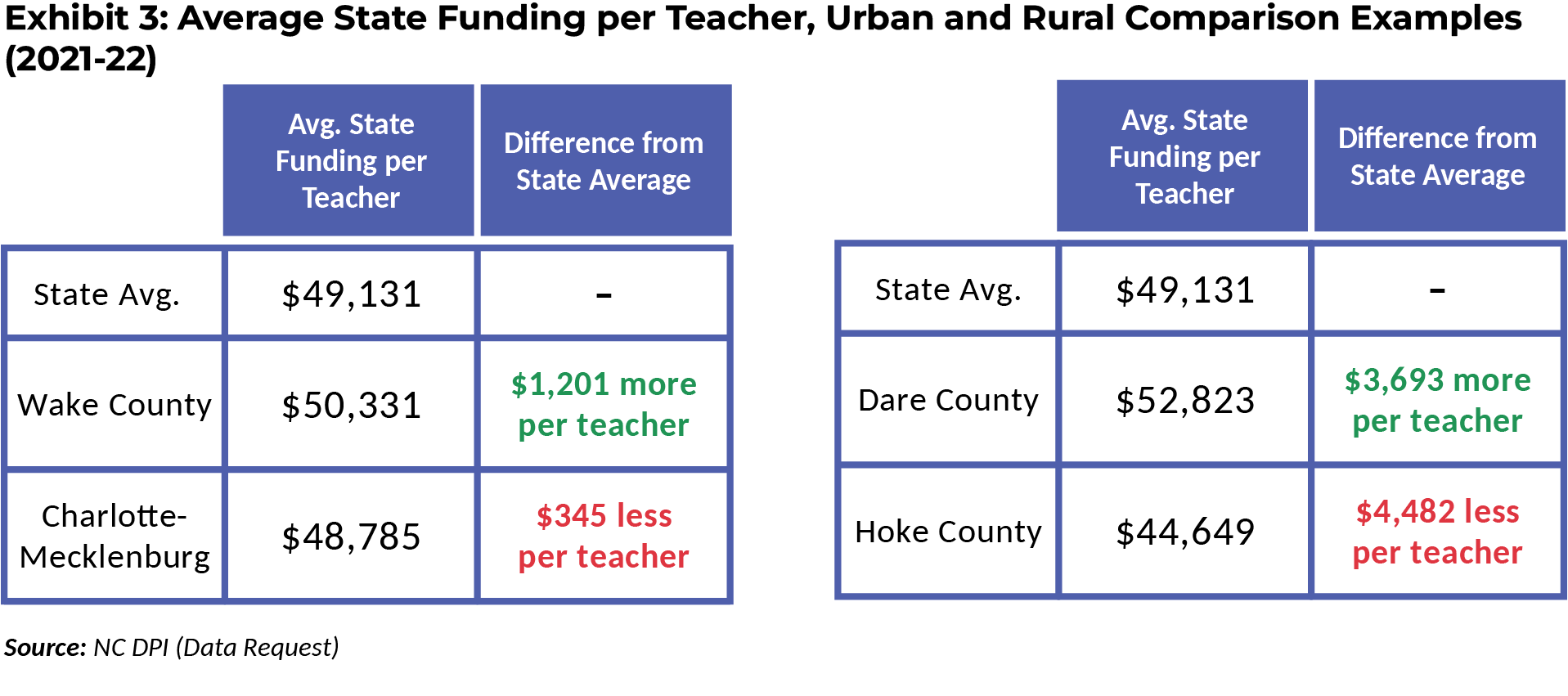

This significant funding inequity that is embedded into North Carolina’s education system comes into clearer focus when comparing a school district’s average state-funded teacher salary to the statewide average for state-funded teacher pay. Below are two examples, one urban and one rural.

With 420 state-funded teachers in Hoke County and 7,719 in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, these districts received $1,948,997 and $3,874,047 less funding, respectively, in 2020-21 than if they had received dollar allotments for teachers based on the average state pay.

With that additional funding, Hoke County could, for example, pay every teacher $4,638 more, making themselves more competitive with surrounding districts that have higher salary supplements, or could use a portion of those funds to establish significant financial incentives to attract teachers into hard-to-staff schools and subjects.

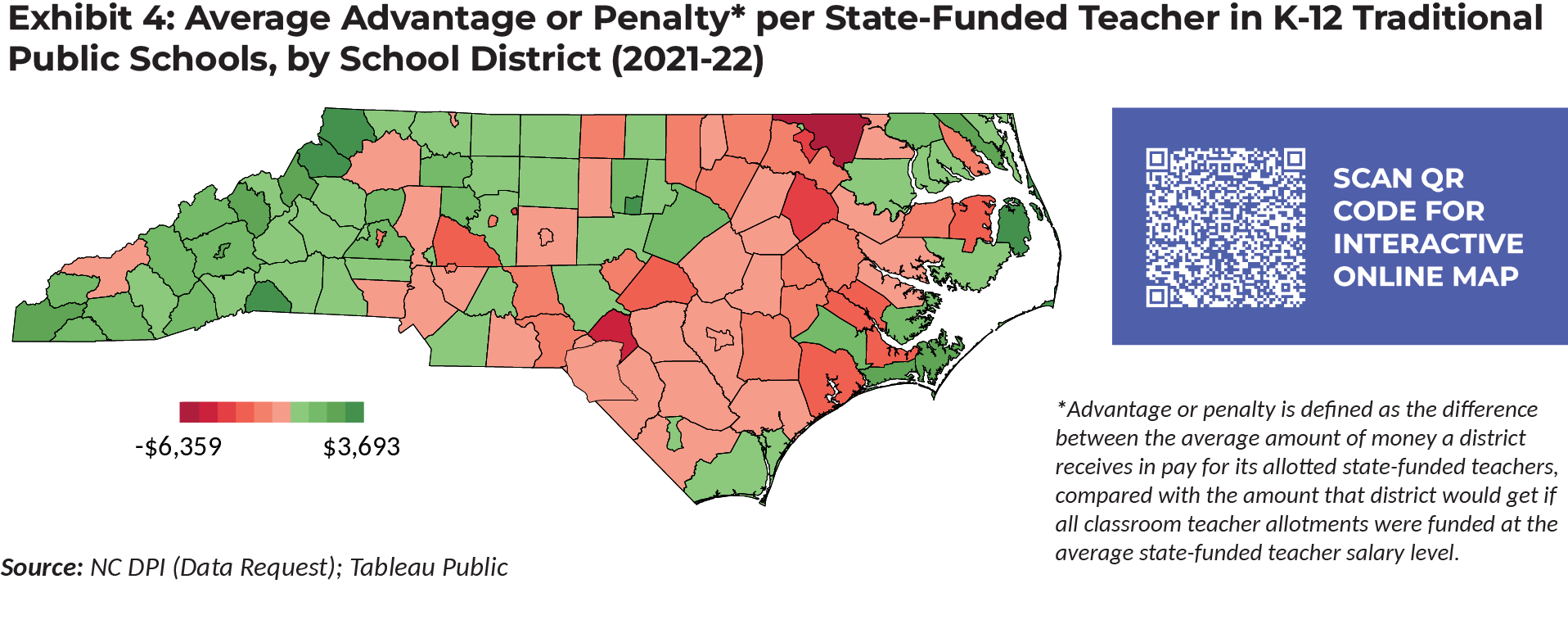

When districts’ state-funded teacher pay advantage or penalty is plotted, there are distinct geographical patterns (see Exhibit 4 below). However, there is no guarantee that a district that is benefitting from this model today will continue to have that advantage in the future. These patterns may shift over time as the teacher pipeline changes in different parts of the state, e.g., as veteran teachers retire and are replaced with less experienced teachers.