Best Practices in Teacher Pay: Front-Loading Base Pay, a Key Strategy for Teacher Compensation

A comprehensive, professional compensation plan includes layered pay strategies that build on one another to ensure the recruitment and retention of a high-quality workforce. This is the fourth in a series of blogs highlighting best practices in teacher pay featured in detail in BEST NC’s report, Teacher Pay in North Carolina: A Smart Investment in Student Achievement.

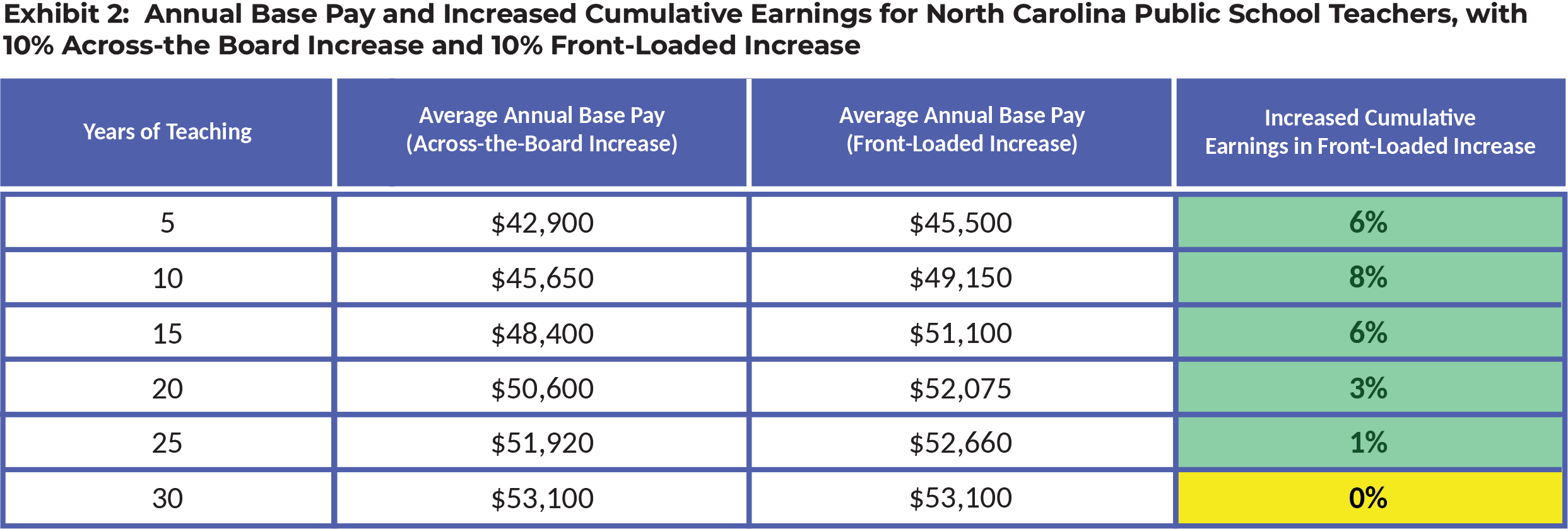

In the first three parts of our teacher pay blog series, we examined three key reasons to include front-loaded base pay in any strategic teacher compensation model. To recap:

- Front-Leading Base Pay for Professional Growth: A front-loaded base pay aligns salary increases to the times in a teacher’s career when they are making the greatest gains in effectiveness, and can act to limit teacher attrition, which is highest during the early part of teachers’ careers.

- Front-Leading Base Pay to Provide a Living Wage: A front-loaded pay schedule would help address biological pay motivators – the need to reasonably support oneself and one’s family through a living wage, particularly at the point where one is likely to be growing their family.

- Front-Leading Base Pay, A Common Practice for High-Skilled Professionals: A front-loaded pay schedule better aligns with other high-skilled professions and is needed to recruit top-tier talent into the teaching profession.

Front-Loading Base Pay to Mirror Other High-Skilled Professions

While discussions of teacher pay often focus on starting salary and maximum salary, the distribution of raises – their size and the years in which they occur – has an outsized impact on teachers’ ability to meet the financial challenges that come with starting and growing a family.

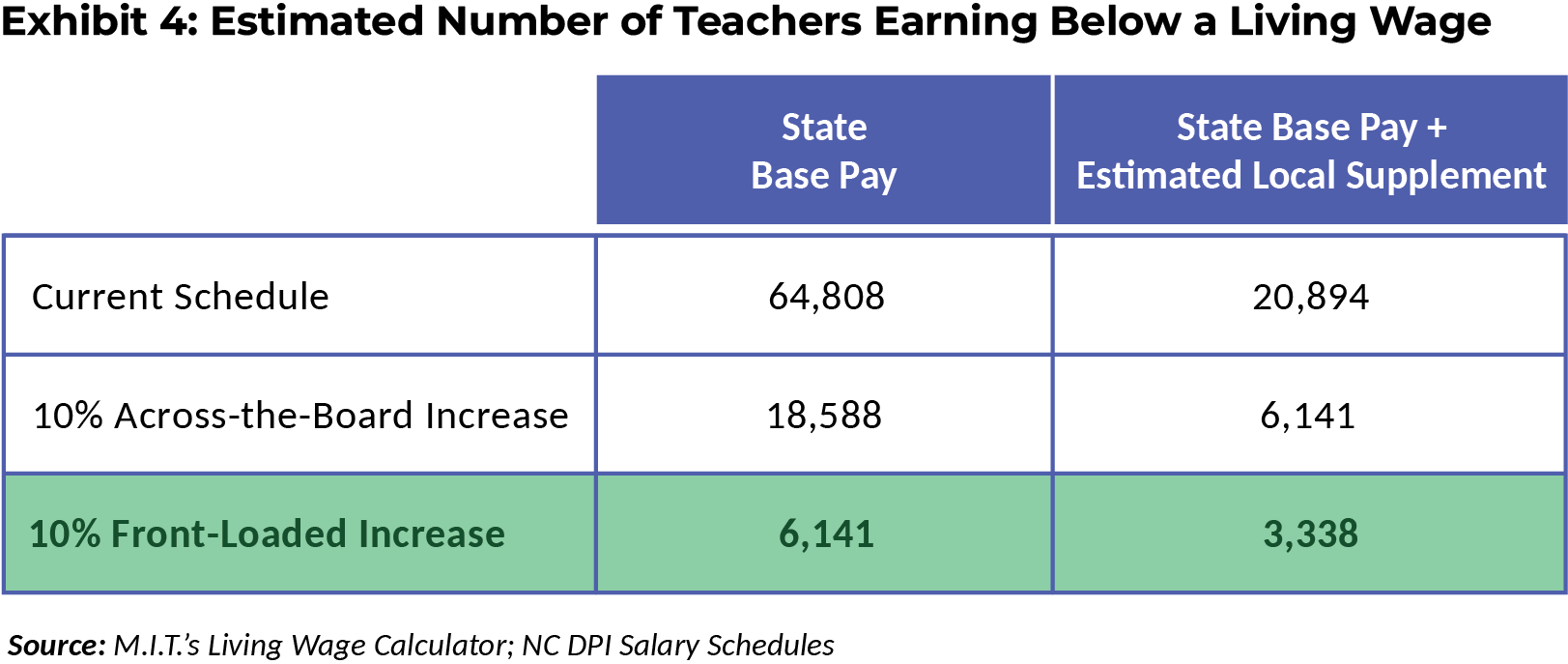

In Exhibit 1 below, we examine the cumulative earnings of two teachers working under different salary schedules. Each schedule incorporates a 10% increase in state spending on teacher pay, but structures the raises differently. In the first example, we apply a 10% across the board increase to the existing state salary schedule in which teachers reach their maximum base salary at year 25. In the second example, we utilize a 10% increase in state spending to front-load the salary schedule so that teachers reach their maximum base pay at year 10.

Over a 30-year career, the lifetime earnings of these teachers are equivalent. However, owing to significant raises in the front half of the schedule, the teacher in the front-loaded compensation model earns 8% more in their first 10 years than the same teacher working under the traditional salary schedule. Higher earnings in the first ten years of a teacher’s career, when they are establishing their families, allow them to keep up with the rapid increases in expenses that come along with having children, purchasing a home, and other costs associated with starting a family.

Note: Other components of salary, including bonuses, National Board-Certified Teacher supplements, and local salary supplements are not considered in this analysis.

.

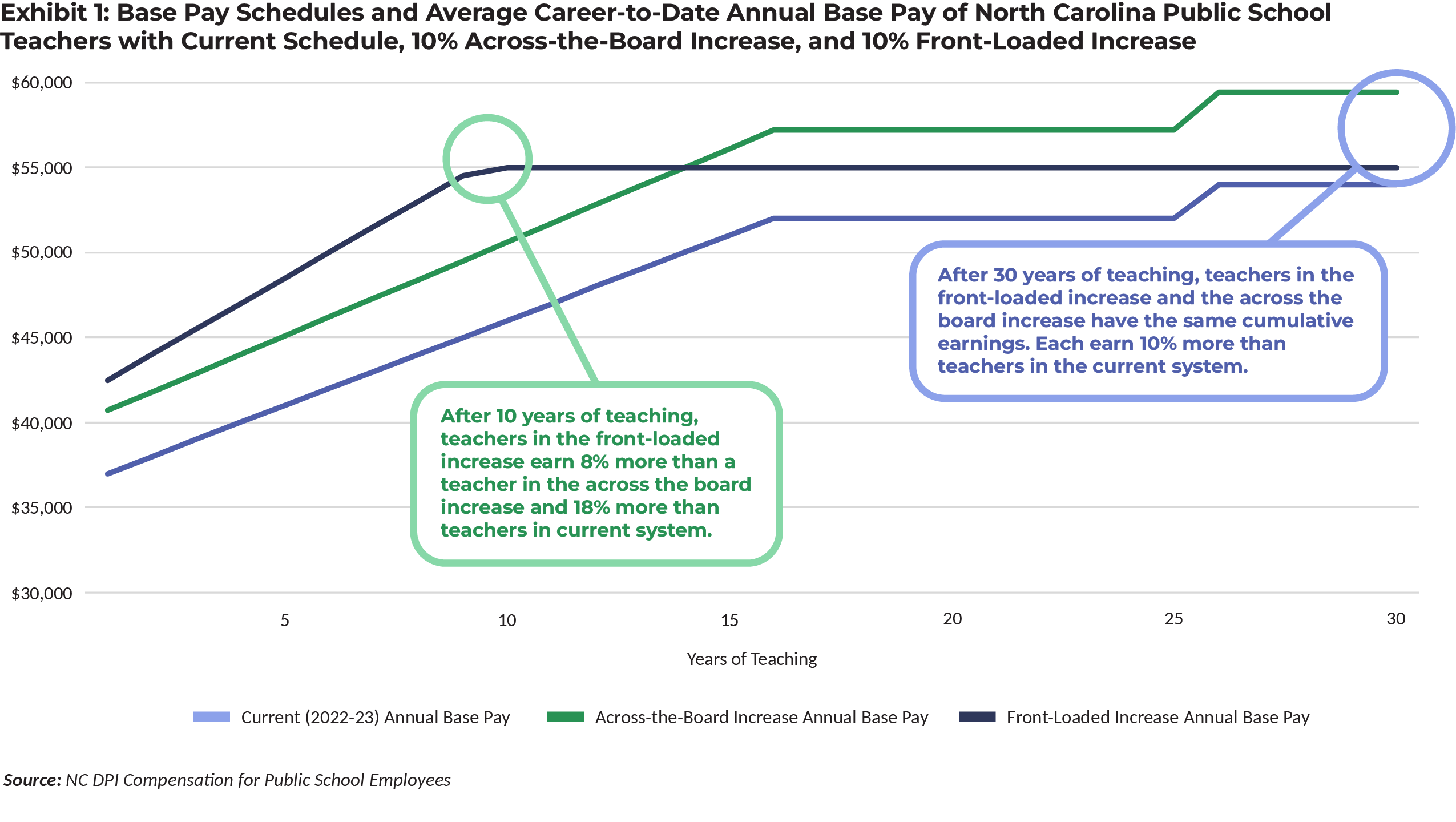

Exhibit 2 below shows the average base pay and cumulative pay increases, at five-year intervals, for teachers receiving across-the-board and front-loaded pay increases.

Note: Other components of salary, including bonuses, National Board-Certified Teacher supplements, and local salary supplements are not considered in this analysis.

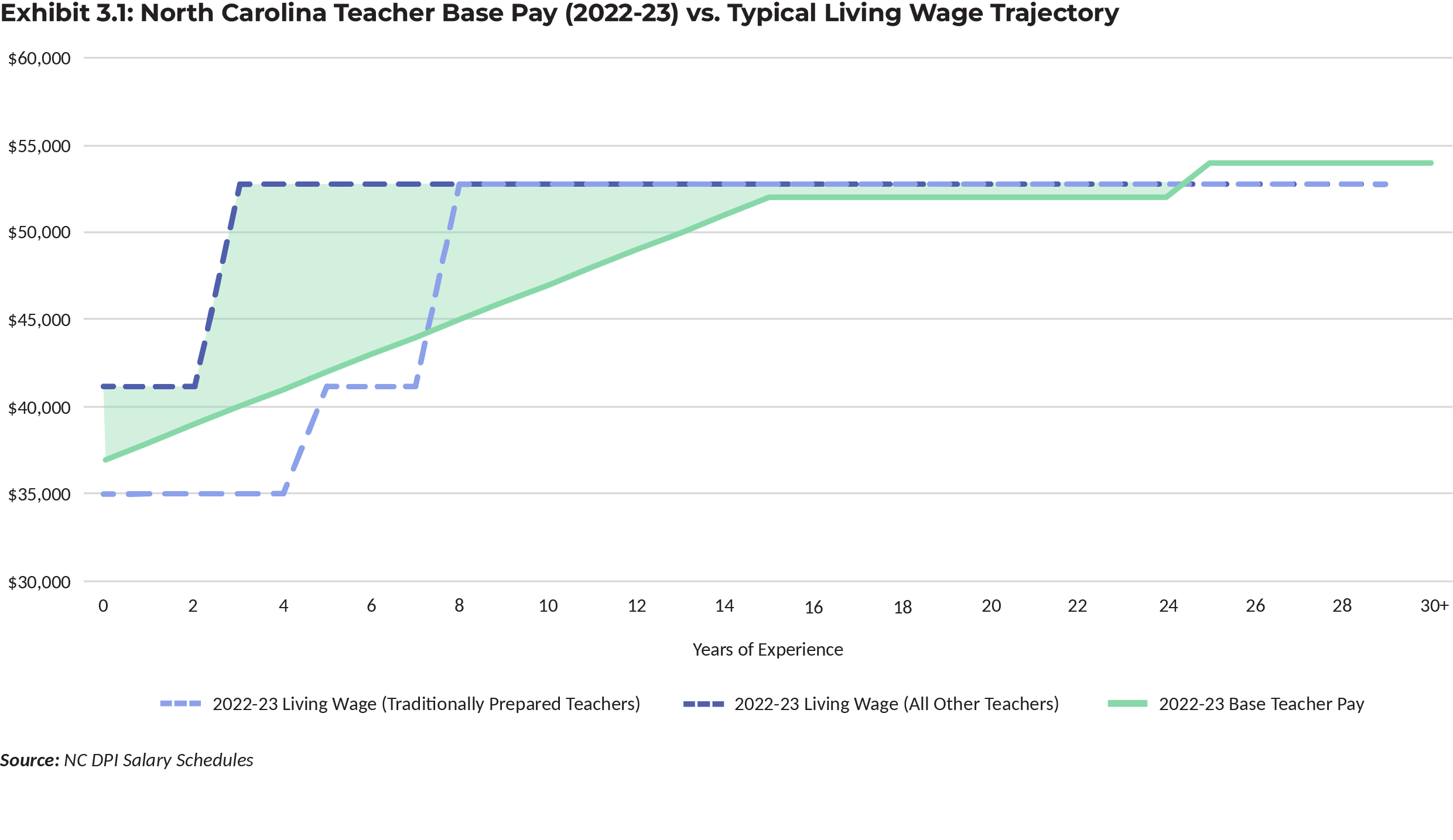

The exhibits below illustrate how a 10% increase in state spending on teacher pay can work to shrink the living wage gap for teachers. First, Exhibit 3.1 shows the existing state salary schedule for teachers and the typical living wage trajectory. The green shaded area illustrates that, when looking only at state base pay, an estimated 64,000 teachers currently fall in the living wage gap.

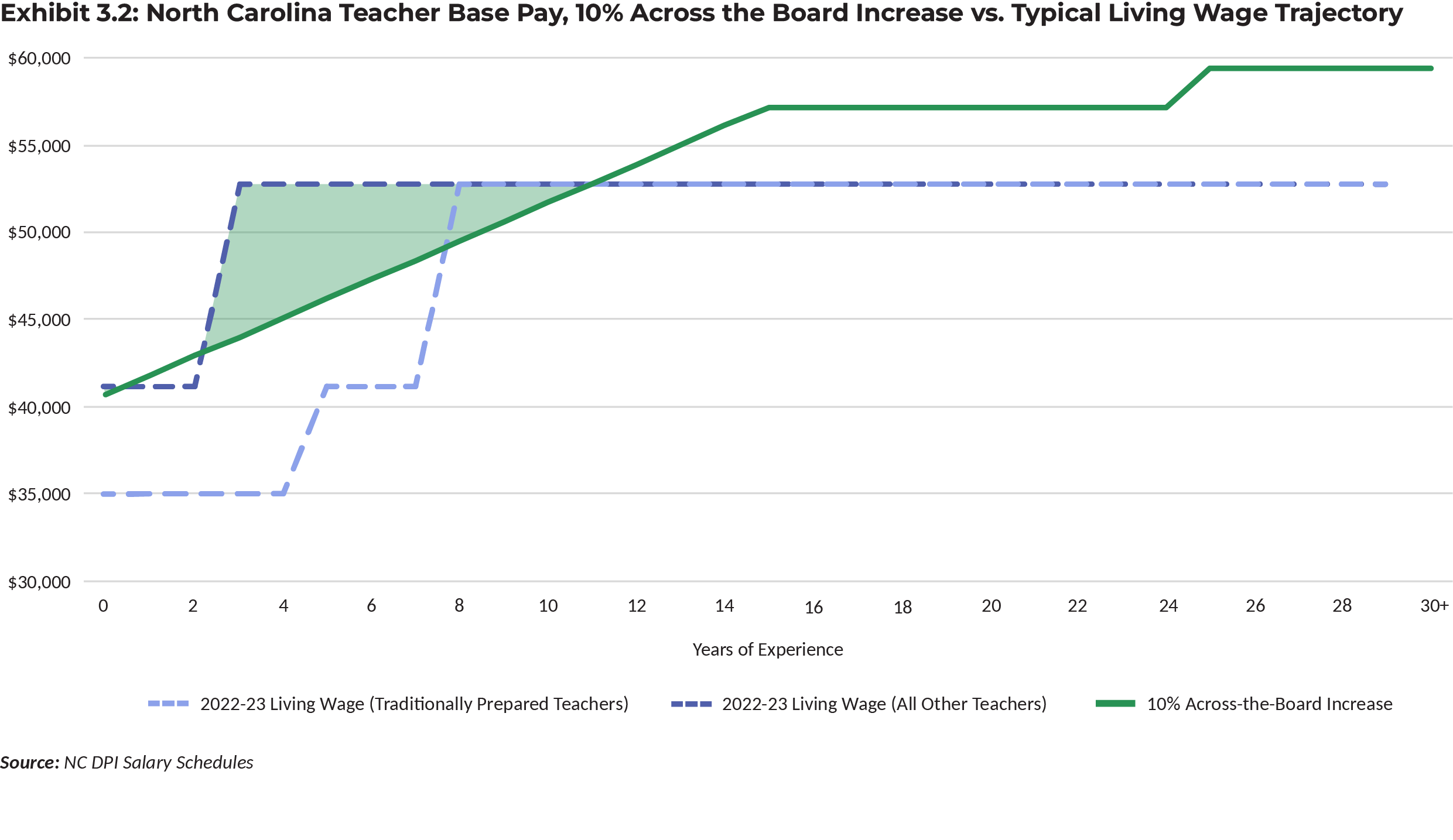

When a 10% increase is applied evenly across the current salary schedule, an estimated 18,500 teachers still earn less than the living wage when accounting for only their state base pay.

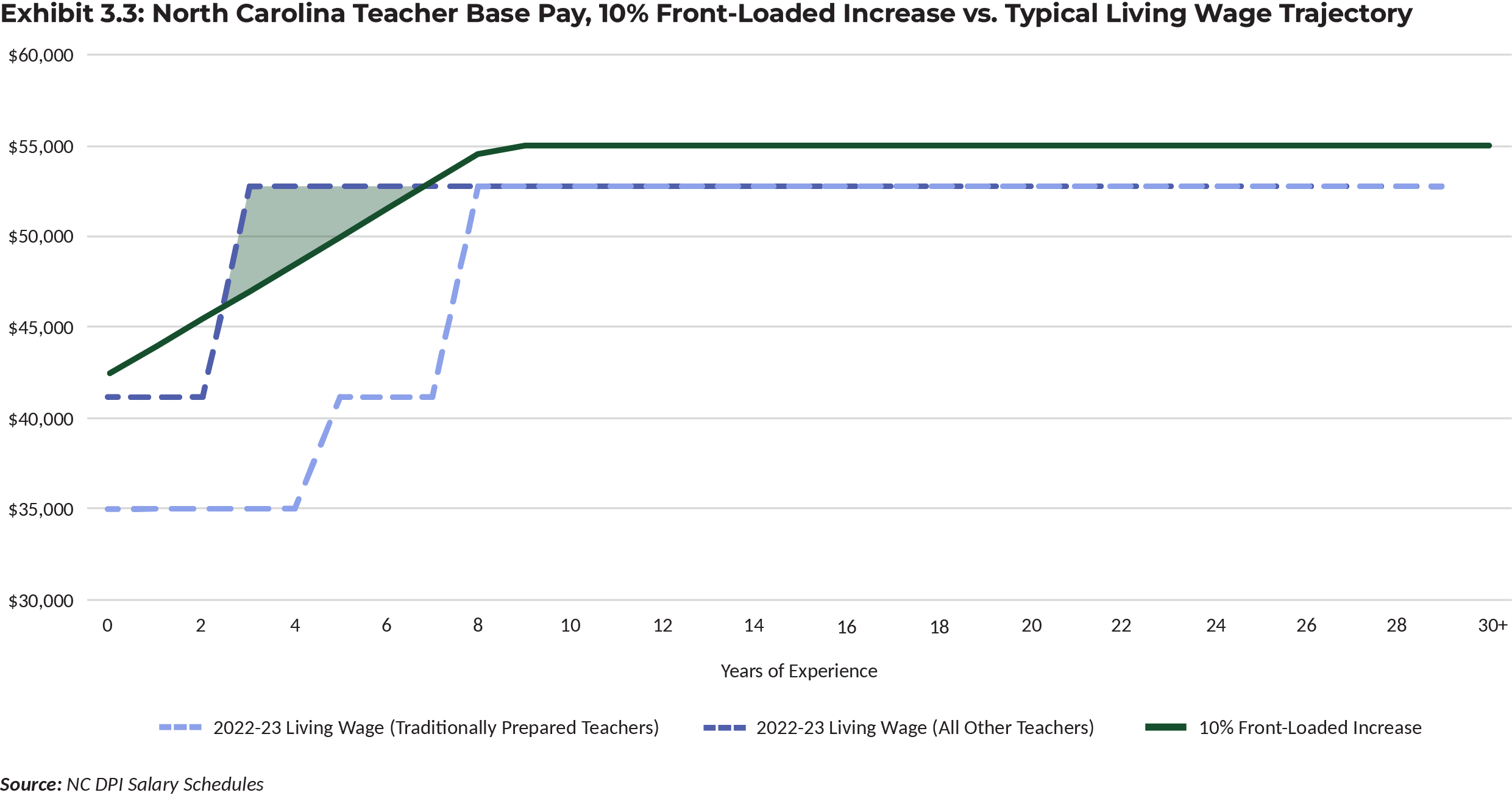

By comparison, making the same 10% investment in a front-loaded salary schedule would leave around 6,000 teachers with state base pay that is below a living wage.

Note: Does not include local supplements.

Note: Does not include local supplements.

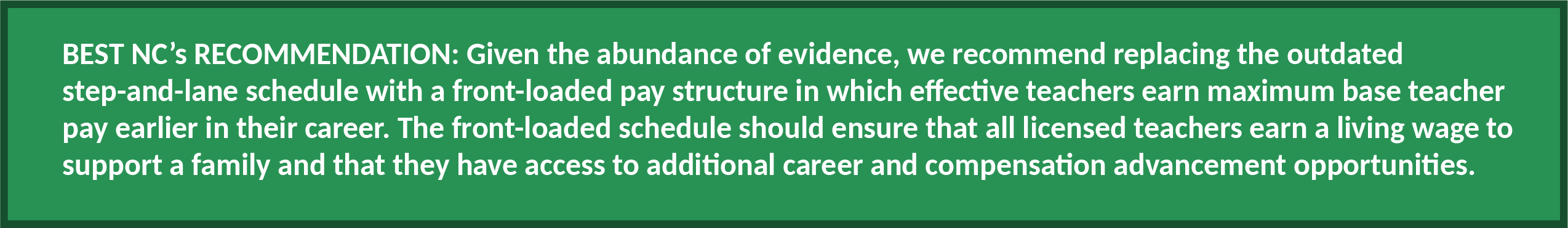

This illustration clearly shows that teacher pay increases that front-load the state salary schedule reduce the living wage gap by greater magnitudes, helping early career teachers better meet financial challenges that come with starting a family. The estimated number of teachers whose base pay and total pay (including local supplements) is below a living wage for the current schedule and in each of the two 10% investment scenarios can be found in Exhibit 4.