Best Practices in Teacher Pay: Differentiated Pay Landscape and Best Practices

A comprehensive, professional compensation plan includes layered pay strategies that build on one another to ensure the recruitment and retention of a high-quality workforce. This is the ninth in a series of blogs highlighting best practices in teacher pay featured in detail in BEST NC’s report, Teacher Pay in North Carolina: A Smart Investment in Student Achievement.

The previous two blogs (one and two) in our teacher pay series have examined how differentiated pay models can be used to increase access to highly effective teachers and improve student achievement in hard-to-staff schools and subject areas. In this blog, we provide an overview of the differentiated pay landscape in North Carolina and the United States and discuss the features of well-designed differentiated pay models.

The Differentiated Pay Landscape

In his report on the long-term trends in the quality of teachers, Sean P. Corcoran notes that “targeted pay increases in specific settings such as hard-to-staff subjects or schools have shown considerably more promise than merit–based bonuses.” Research shows that providing bonuses to recruit and retain teachers in hard-to-staff subjects and schools can significantly reduce teacher turnover in those positions, helping to reduce vacancies. Importantly, the size and sustainability of these efforts significantly affects their impact, which is covered below.

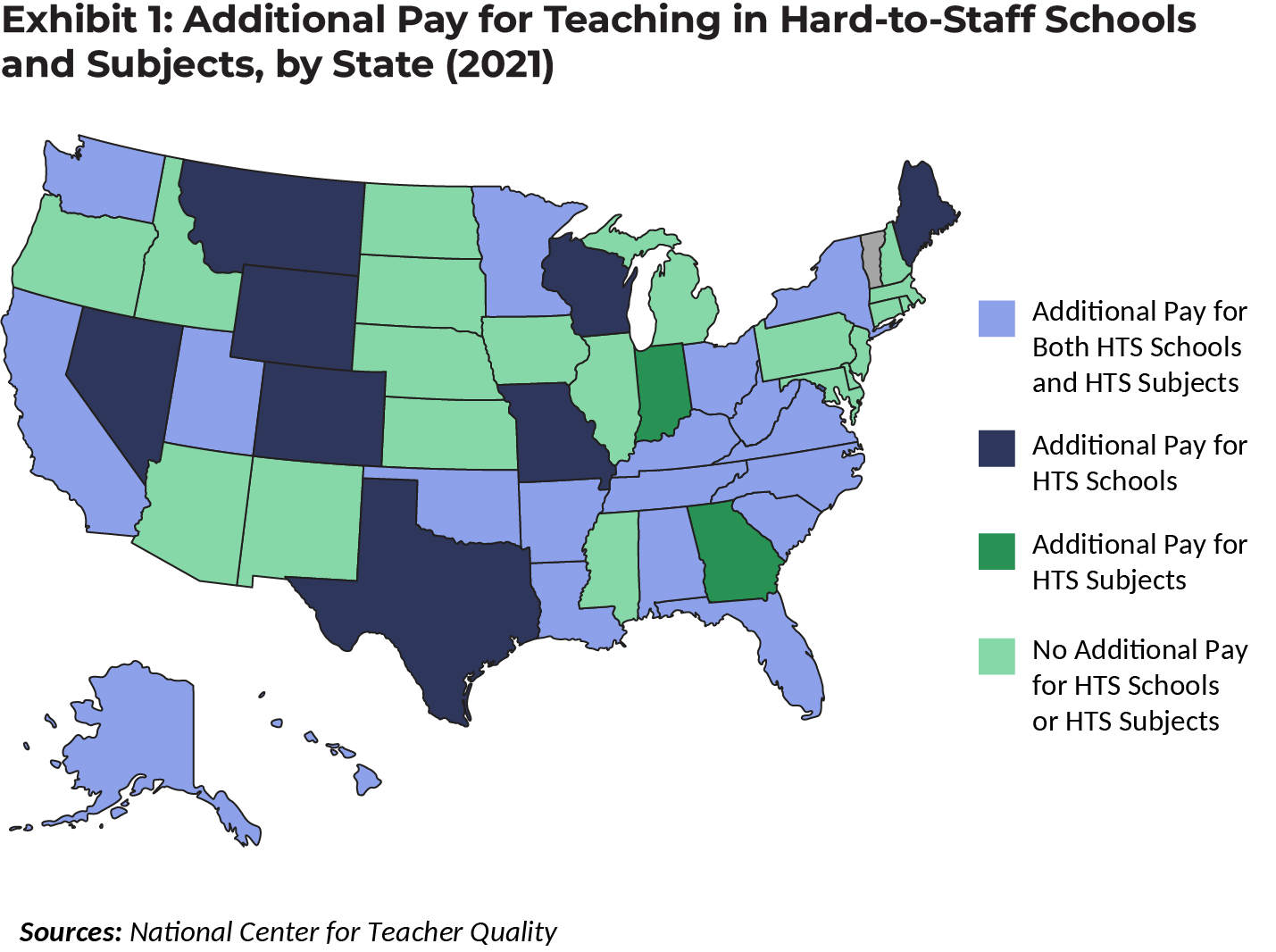

Currently, 32 states incentivize teachers to work in high-needs schools using either additional compensation, loan forgiveness, or both. Meanwhile, 34 states offer additional compensation, loan forgiveness, or both to incentivize teachers to teach hard-to-staff subjects.

In North Carolina, there are several ways in which pay incentives are used to recruit teachers to work in hard-to-staff schools and subject areas:

- Highly qualified graduates of in-state educator preparation programs are eligible for salary increases during their first three years of service. Eligible teachers working in low-performing schools are paid the salary of a fourth-year teacher during their first three years of service, and eligible teachers working in Special Education or STEM positions at any school are paid the salary of a third-year teacher for their first two years of service.

- While not a pay incentive, scholarship programs can be an effective recruitment incentive. The North Carolina Teaching Fellows program offers a forgivable loan of up to $4,125 per semester for those enrolled in participating educator preparation programs. Eligible candidates must pursue certification in Special Education or a STEM subject, and accelerated forgiveness is available for teachers who elect to teach in low-performing schools.

- Beginning in 2021, North Carolina invested $4.3 million to provide low-wealth and small county recruitment bonuses of $1,000 per teacher in school districts that receive funding through the Small County or Low-Wealth allotments. State funding must be matched 1:1 with local funding and signing bonuses may be up to $2,000 per teacher.

.

Each of these efforts is promising but has limited reach, with only a small subset of teachers affected.

The Importance of Size and Sustainability

The research makes clear that differentiated pay is most effective when it is significant, recurring, and sustainable.

Many industries, including the military, offer substantial financial incentives to fill hard-to-staff positions. According to education think tank Public Impact, “The cross-sector research does not offer a concrete formula for determining the most effective level of hard-to-staff incentives. What is clear, however, is that employers across sectors are providing much larger incentives than the majority of hard-to-staff pay programs in education. Incentives between 10 percent and 30 percent of a teacher’s salary would be more in line with other sectors.”

Differentiated pay for teachers in hard-to-staff schools and subjects can take many forms, including one-time bonuses, annual salary supplements, student loan forgiveness, tuition reimbursement, and mortgage assistance. State-level studies in North Carolina, Washington, Georgia, and Tennessee have documented the effects of these differential compensation strategies on teacher recruitment and retention in hard-to-staff schools and subjects. Key findings include:

-

- Stipends and bonuses in these state-level studies proved to be effective at retaining teachers across a number of contexts, including low-performing schools, high-poverty schools, and in hard-to-staff subjects.

- Recruitment and retention benefits of these programs generally last only as long as teachers are receiving the additional compensation, suggesting that one-time bonuses are not as effective as annual stipends or increases in base salaries.

-

- The amount of additional compensation matters. While not offering a precise amount, studies of salary bonuses and loan forgiveness programs for teachers working in hard-to-staff schools and subjects have found that larger bonuses or larger amounts of loan forgiveness are effective at recruiting and retaining teachers, while smaller bonuses and smaller amounts of loan forgiveness are less successful.

- The perception of sustainability also matters. An analysis of Washington, D.C.’s teacher evaluation and performance pay-differentiated pay framework (DC IMPACT) suggested that, in IMPACT’s first year, its effects on teacher performance and retention were significantly muted relative to those same effects in the program’s second year. As the program became more established and incentives were perceived to be more durable, the program began to more reliably produce changes in teacher performance and retention.

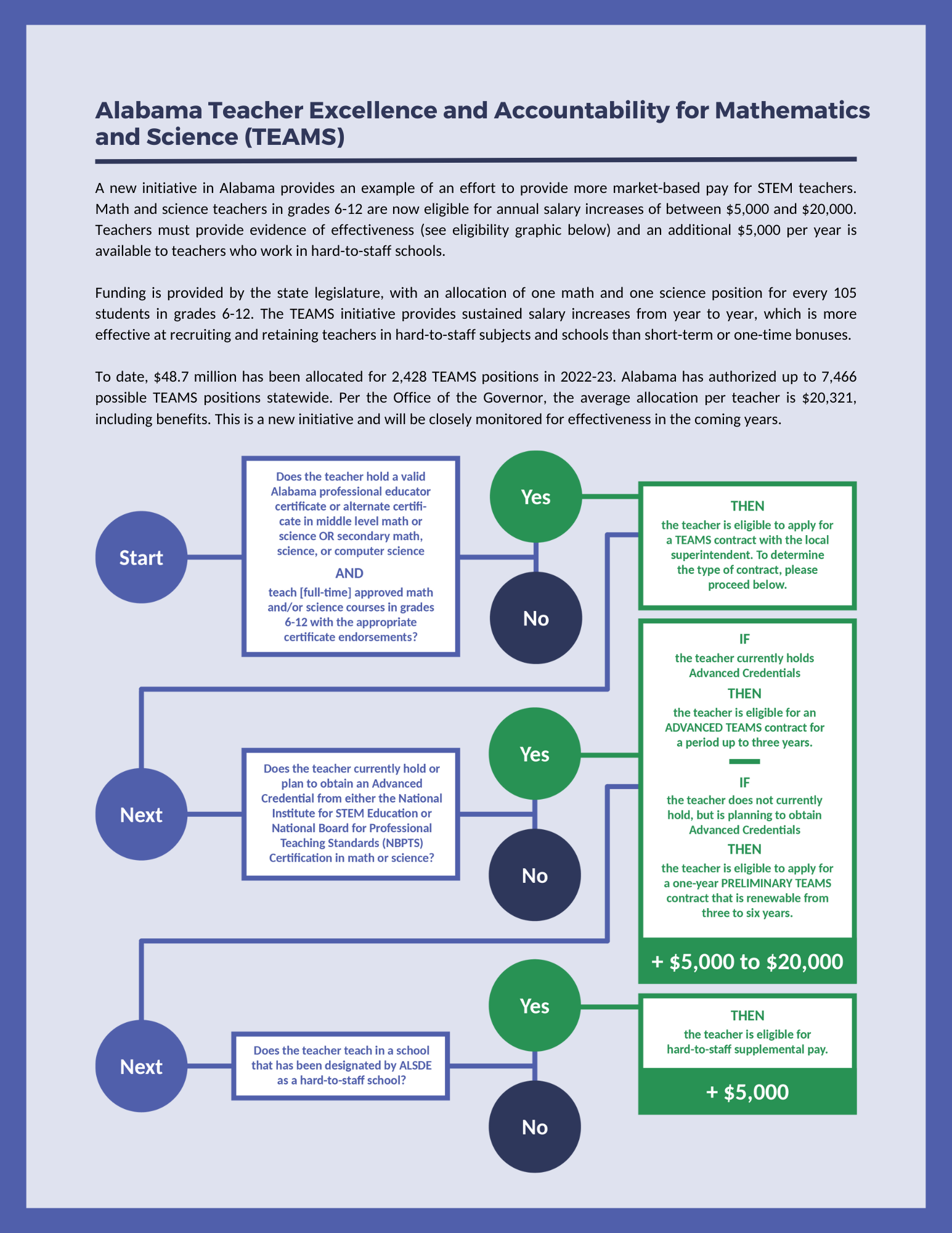

An example of a differentiated pay policy aligned with best practices is underway in Alabama: